The following article was published in 1973.

For his 100th Birthday

By Arne Thorne

Since Rudolf Rocker's birth on March 25, 1873 in the old city of Mainz on the Rhine river, until today, the world has changed tremendously. It's no exaggeration to say that the political, social and scientific changes and turnovers during the past 100 years have altered this epoch more efficiently than the social development of 2000 years since the foundation of Rocker's home town in ancient Roman times.

There have been turnovers in Rocker's life too. The family he was born in was Christian and his mother was faithfully Catholic. Rocker became an orphan at a very young age. His conscious life began in a Catholic, military-like orphanage, where he received his elementary education and where his rebellious nature collided more than one time with his sadistic overseer, who brutally ruled over the children. In this prison-like orphanage he developed his stubborn nature. It was a similar situation like when he, a bitter enemy of the German Kaiser and all Prussian nobleman, got imprisoned in an English concentration camp during the First World War. For the English militarists, Rocker had the same sympathy as for his "own" war mongers. In their great wisdom they thought Rocker would support the German Kaiser although Rocker had agitated against war in his anti-militarist articles long before it begun.

Under the influence of his uncle, Rocker turned out to be a bookbinder and socialist at the age of 15. But three years later he became an anarchist. Before he reached 20, he needed to flee from the German police into another country because he committed the crime of anarchist propaganda, which was forbidden in Kaiser Wilhelm's country at that time.. He left Mainz directly from his workplace where the police tried to catch him and went to Paris in 1893. There he met Jewish anarchist workers for the first time in his life.

Jewish workers and anarchists - this was a double surprise to Rocker. The Jews Rocker knew from his home town Mainz had been retailers or self-employed. There is no doubt that the revolutionary activist had no contact with them. But the Jewish workers and anarchists in Paris attracted Rocker very soon. In particular their language, which the young German understood and at the same time didn't understand, fascinated him. The Yiddish language was the third surprising discovery he made.

When Rocker moved from Paris to London after a couple of years, he immediately contacted Jewish workers and anarchists, who already knew him from his activities in Paris. And there begun 20 years of creativity, organisation and education among the Jewish immigrant masses in England, who mostly left London after some years to go to America, Canada, South Africa, Australia and other countries of the world. Rocker's intense and colourful work in the Yiddish language, which the young German spoke fluently, influenced thousands of Jewish workers who founded clubs, unions and experimental communes in various countries.

Rocker did not turn into a master of the Yiddish language over night. When the 25-year old Rocker went to London he met German anarchists. When he came to London 75 years ago he met German anarchist who had good contacts with Jewish anarchists in London. There have not only been Jewish anarchists in London but also in other bigger English cities. By accident, Rocker visited the meeting of a Jewish-anarchist group in Liverpool. These comrades had the plan to publish an organ named Dos fraye vort. Everything had been prepared. There was just one thing missing: an editor. One of the comrades proposed Rocker. The surprising German thought this was a joke. But all participants agreed on the proposal and supported it enthusiastically. And they told him not to be concerned about his Yiddish skills. He could simply continue writing German and they would translate it into Yiddish.

Rocker agreed on the proposal with mixed feelings. But he realized that to do his work perfectly he needed to learn proper Yiddish. And he learned Yiddish so well that he got offered the post as editor of the Arbeter fraynd in London and after that he got offered the editor position of Zsherminal, a theoretical and literary journal. And so Rocker created important literary and theoretical works in Yiddish, which have mostly not been translated into German until today. If those texts would be translated, it would probably reach the popularity of his German writings which Rocker created between the two wars and which have been translated into French, English, Italian, Spanish,. Portuguese, Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Netherlands, Russian, Polish, Czech, Bulgarian, Japanese and even into Esperanto.

But Rocker's oral influence on Jewish workers was even greater. Rocker did not only talk about anarchism and other socialist topics, such as the necessity to form unions for Jewish workers during the bitter strikes in England, he also spoke about literary, scientific and artistic topics. Some of the topics Rocker talked about are "Intellectual Intentions of Our Time", "Modern Literature", "Astronomy", "History of Ancient Greek Art", "India", "Stanislaw Pshibishevski and the Problem of Sexuality" and more like that. The intelluctally hungry Jewish workers devoured his words about international classics like Ibsen, Strindberg, Zola, Franz, Mirbo, Multatuli, Hauptman, Nietzsche, Goethe, Schiller, Maeterlink, Ibanez, Cervantes, Wild, Shelly, Byron, Wild, Shakespeare, Tschechov, Tolstoi, Andreyev, Gorki and others.

Rocker gave those lectures, courses and speeches in front of a various number of people from six to seven thousand in a big hall in London or in front of six people. One of the listeners was Alexander Granach, a Jewish-German actor, who had been anarchist in his younger life and who kept being devoted to Rocker until the end of his live. There were thousands of Jews who remained devoted to the Yiddish speaking and Yiddish writing German until the end of their lives.

These creative and wuthering years among Jewish workers in London were full of odd incidents, funny and interesting episodes. We will remember just one of them: Anti-Semites in Whitechappel used to call Rocker "Jew" and "Christkiller", while at the same time religious Jews cursed him publicly. Rocker simply smiled and continued to bring colours into the grey lives of the Jewish masses.

Once when we were talking about the London' years I asked him why he became so attracted to Jewish workers and why he tried to improve their intellectual and economic situation for 20 years long. Rocker answered:

When I came to London, I met organised groups of German anarchists, professionals with good jobs and members of English trade unions. They had their own organs, the possibility to learn new languages, access to social literature and to the art and literary creations of other people. But the situations of the Jewish workers was completely different. They lived in a neglected but fruitful situation which gave me the possibility for work which deeply satisfied me. I didn't do it to stay above the poor Jewish workers but to help them intellectually and socially. I loved to work for the cause of the Jewish workers and the Jewish comrades accepted it with great gratitude.

100 years after Rocker's birth just a few of his comrades remain alive. But those who remained are still deeply influenced by Rocker's thoughts and there are those who didn't know or listen to him personally but who got by influenced Rocker's writings.

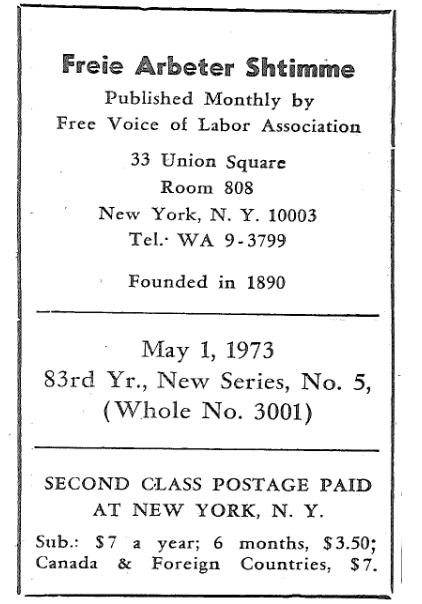

Arne Thorne. Rudolf rokers hashpoe oyf yidishe arbeter. in: Fraye arbeter shtime. Vol. 3001 (May 1973), New York: Free Voice of Labour Association, 1973.

Translated from the Yiddish language by Marcel